Tanuki or How a Trickster Survived Through Time

Have you seen statues like these in Japan? They are often placed in front of shops, restaurants or homes and are said to bring luck and wealth. These creatures are called tanuki 狸 and they actually exist. In English we call them racoon dogs or, to be more scientifically accurate: nyctereutes procyonoides. But why are tanuki associated with luck nowadays and thus placed at the entry? To understand this we have to dig deeper into their folkloristic origins.

If we go back around 1000 years, at first there seems to be no direct answer to this question: The tanuki was already mentioned in the Konjaku monogatari, a Japanese tale collection from the late Heian period (794–1185), but in these stories the racoon dog was depicted as an evil, demonic creature, as well as a popular target for hunters.

© Mother Nature Network, Stanislav Duben, 2014

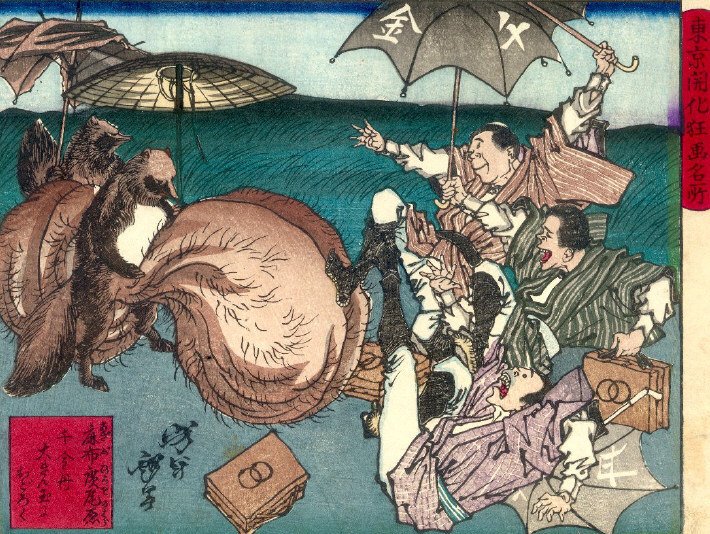

So how did the relation between the tanuki and luck, wealth come into existence? Apparently, what played a major role in how the tanuki was depicted later on and today, are its testicles. Yes, its scrotum, sac, nuts played a major role, literally: Around the second half of the 8th century, the scrotum of the real tanuki, the animal, came to be essential in manufacturing gold leaf – metalworkers in Kanazawa used the malleable skin of the testicles to thin out gold by putting it inside the sac and treating it with a hammer. Symbolically speaking, the act of ‘stretching out’ gold is therefore associated with a wallet becoming wider, money being multiplied, thus, becoming richer. In the 16th century, stories and art revolving around tanuki became very popular. It is not exaggerated to say that artists were obsessed with the illustrations or descriptions of the tanuki scrotum. And the things that these testicles were able to do were sheer endless. On the artworks the skin of the scrotum was so large that tanuki used them as blankets, carrier bags or even fishing nets. In the 1840’s, ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi depicted a tanuki net fishing for geese with its own scrotum. So, it seems that the story of the scrotum’s versatile usage took off in the gold manufacturing sector, but has progressed much further into the fictitious world.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–1892), Tanuki of Hirō Plain, from the series Famous Humorous Places in Tokyo, 1881, woodblock print.

Another aspect of the tanuki’s folkloristic depiction is the fact that it can change its shape. Thanks to its magical powers it can turn into various objects, persons, and even into the moon. This allows the tanuki to play their beloved pranks on people. For example, if they want to drink sake in a bar, they would first shape shift into a human and turn some leaves into ‘money’. However, as soon as they leave the bar, the money will turn into leaves again, leaving the owner with nothing behind. With this in mind, putting a ceramic tanuki in front of a shop is a kind of precautionary measure. This is supposed to make the tanuki tricksters believe that there already is another tanuki playing pranks in that place. Therefore, it would not be worthwhile to choose that spot for its mischief. As said before, in the Heian period tanuki were shown as demonic creatures, but over time their pranks became more and more harmless.

The stereotypical tanuki statue nowadays has some distinctive features: a straw hat as a sign for their vagabond life, a sake gourd, an account book for its debts and, of course, a large scrotum associated with gold manufacturing, therefore related to wealth. Also, it has a round belly, on which it plays the drums. With that drumming sound it can make people feel disoriented, making it easier to play a prank on them. But the roots of the cute, chunky tanuki statues as we know them today are owed to one person in particular: Fujiwara Tetsuzō (1877–1967). Fujiwara was a potter from Shigaraki, Shiga Prefecture. When Emperor Hirohito paid Shiga Prefecture a visit in 1951, the street where the Emperor arrived was lined with tanuki statues holding flags in order to honour him. It amused the Emperor so much that the tanuki as we know them today got another major popularity boost.

Keep in mind, if you ever stand in front of someone whose clothes stay dry even though it is raining – chances are that this is in fact a tanuki disguised as a human.

Written by Jannick Scherrer