A Journey Through History: An Intermezzo of War

10 minutes read

One of the characteristics of Yayoi culture was the establishment of tribal alliances through a hierarchical predominance of stronger and more influential communities. These alliances, typical of Yayoi populations, became increasingly complex during the centuries which were described by Chinese chronicles from 3rd century A.C. as kingdoms (CN: guó, JP: kuni; 國) ruled by chieftains, which are defined as kings by the Chinese epithet (CN: wáng, JP: ō; 王). This process would ultimately spawn the kingdom of Yamato, which became the political base for the constitution of the first Japanese central power in the late 5th and 6th century. The Yamato Kingdom consolidated its power in Nara and established the country’s first proper capital.

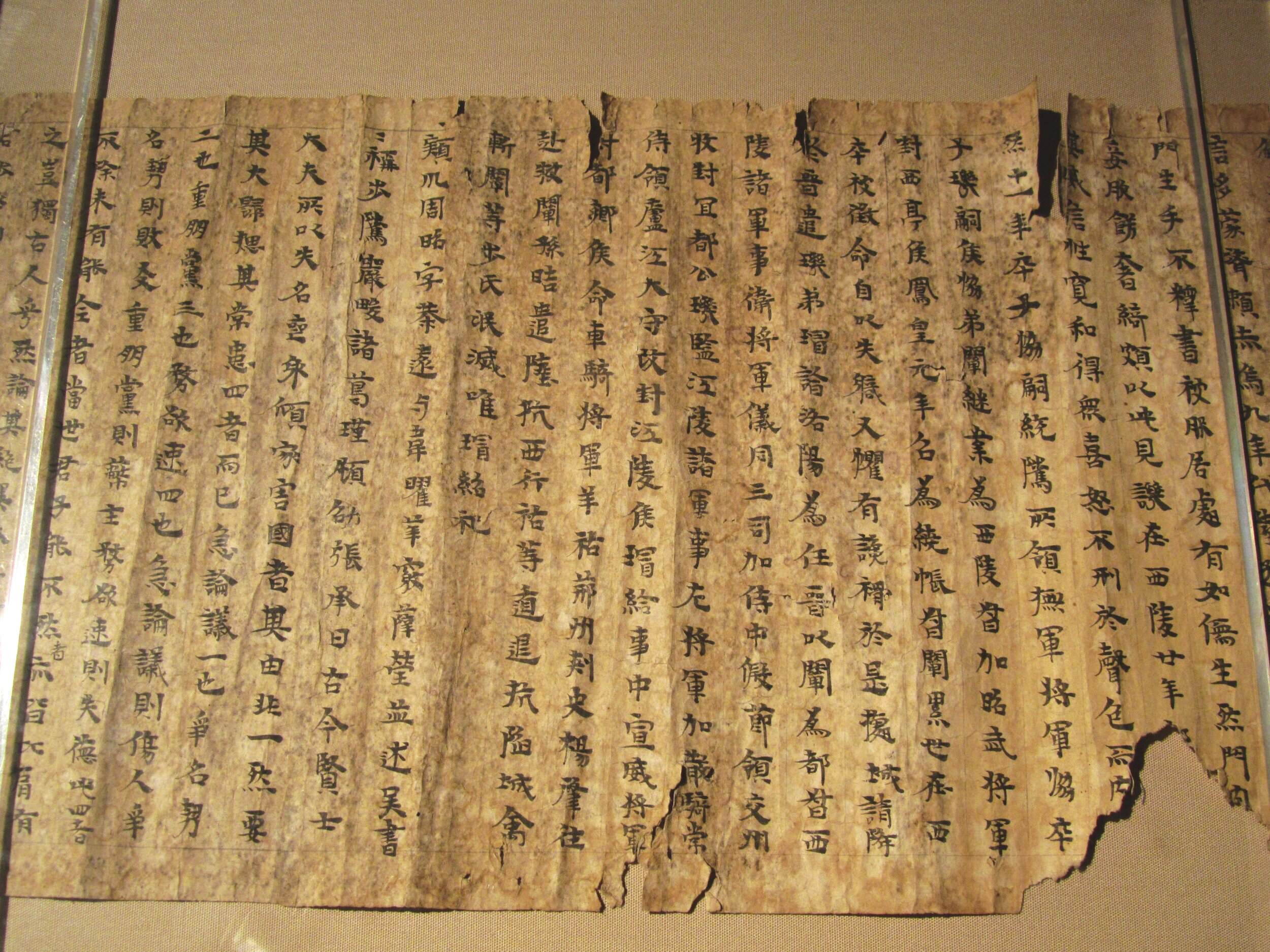

A Fragment of the Books of Three Kingdoms; part of the Dunhuang manuscripts. © 猫猫的日记本

However, it appears that the constitution of said strong chiefdom was achieved through a period of unrest, when tribes violently fought for supremacy sometime between the 1st and 2nd century A.C. Such internal conflicts have been described by Chinese historians in their first mentions of Japan and were confirmed by modern archaeological studies who found evidence supporting the Chinese documents. In a more subtle way, the Japanese national myths, recorded until the 7th century A.C., also mention a period of unrest. However, these stories are a less reliable source for historical information, as they are permeated by the language of legends and myths.

According to the Chinese chronicles, from the initial 100 small kingdoms across the Japanese islands, about 30 stronger ones emerged by federating or subduing their neighbours. Such chiefdoms were scattered from northern Kyūshū through the Inland Sea, up to the Kinai region, and among them were the legendary Izumo and the mythical Yamatai, which will be discussed in a dedicated article. Now, we will focus on this transitional period by presenting three complementary approaches to the same topic, the historiographical critique of Chinese sources, the archaeological interpretation of specific sites, and the symbolic interpretation of what has been represented through the Japanese myths.

A simplified map highlighting some relevant regions for Yayoi culture at the time.

Base map provided by Google, infographic effectuated by Marty Borsotti.

The Chinese Sources: the First Historical Chronicle of Japan

The very first historical document mentioning the happenings in the Japanese archipelago have been compiled by Chinese historians during the 3rd century A.C. A section of the Sānguó Zhì (History of the Three Kingdoms 三国志 between 280 and 290 A.C.) called Wei zhi (History of the Kingdom of Wei 魏志 ) includes a passage dedicated to the people of Wa (Wajinden 倭人伝). The islands of Kyūshū and Honshū were both defined as the ‘land of Wa’ in a rather derogatory fashion. The first ideogram used was interpreted as bearing the meaning of ‘dwarves’ and was later replaced by its common graphism of Yamato 倭 and Harmony 和.

The incipit of the Wajinden reads ‘the Japanese people (the Wajiri) are located in the Lo-lang seas, have more than 100 states, and are periodically received [at the Lo-lang court]’.

Wajinden is a relatively short text with only 2000 characters, yet it offers an astounding political and ethnographic documentation of the populations dwelling on the Japanese islands. It was likely composed by gathering the reports of Chinese envoys sent to the land of the Wa to broaden the network of the mainland rulers, as well as collecting the pieces of information brought by chiefdom ambassadors who had direct connections with the continent. According to this chronicle, peoples and tribes acted within a complex system of hierarchical dynamics which structured both village sociality and relations among tribes.

‘The Wa people live on mountainous islands in the middle of the ocean southeast of Daifang. Earlier, more than one hundred chiefdoms were seen at the imperial court in Han times. Now envoys and interpreters of thirty of their chiefdoms go back and forth. […] Going for the first time over the sea more than one thousand li one arrives at the Tsushima chiefdom. The high official is Hiko and the subordinate Hinamori. This isolated island may be more than four hundred li square. The land has steep hills and dense forests, with roads like bird and deer paths. There are more than a thousand households. The rice fields are not good, so they naturally live on seafoods. They travel by boat to buy grain in markets to the north and south. Again, crossing south more than one thousand li over the sea named Han-hai one arrives at a large chiefdom. The official is Hiko and the subordinate Hinamori. It may be three hundred li square, and has many bamboo trees and thick forests. There are about three thousand families. They cultivate rice fields, but they need still more and also make up the shortage of food by buying grain in markets to the north and south. Going again across the sea for over one thousand li, one arrives at the Matsura chiefdom. There are more than four thousand households who live along the mountain foot and seacoast. The grass and trees are so luxuriant that a person walking in front cannot be seen. The people are fond of catching fish and collecting abalone; regardless of shallow or deep water all go down to catch them. Going southeast on land five hundred li one reaches the Ito chiefdom. The official is Niki, the subordinates Imoko and Hikoko. There are over one thousand households, ruled by a hereditary king. These people are all subjects in the queen’s domain. When an envoy from the commandery comes and goes he always stays at this place. Going southeast a hundred li is the Na chiefdom. The official is shimako, the subordinate hinamori. There are more than twenty thousand households […].’[1]

Mentions of Internal Warfare

The Wajinden, as well as a later historical compilation known as Hou Han shu (Book of Later Han 後漢書 5th century A.C.), mention how the relatively peaceful 3rd century in Japan was preceded by a period of internal conflicts which lasted throughout the 1st and 2nd centuries A.C. The two sources contradict each other regarding the exact duration and time frame of the internal troubles: the Wajinden speaks of a span of eighty years, while the Hou Han shu reduces it to forty years. A later chronicle, the Liang shu (Book of Liang 梁書 635 A.C.) identifies five critical years, between 178 and 183 A.C., where the conflict was at its peak. Whether this period involved several generations or just one, it led to the end of Yayoi culture. A new typology of societies and cultures emerged, which were named after their burial practices: Kofun 古墳, key-hole shaped funeral mounds reserved for important rulers. By this stage, political power was concentrated in the hands of a few chieftains, who managed to gather important populations under their command and expand their territories. Among those people was the famous, even legendary, emperor Jimmu, mentioned by the first Japanese mytho-historical chronicles Kojiki (古事記 712 A.C.) and Nihon-shoki (日本書紀 720 A.C.).

Handmade copy of a page of the Kojiki (1371).

Reproduction of the Golden seal with the inscription 漢委奴國王 ([the Dynasty] Han, [Land of] Wa, [Kingdom of] Na, State, Ruler), probably hinting at an official recognition from the Han emperor of the authority of the King of Na over his kingdom.

Some regional rulers are mentioned by the aforementioned Chinese chronicles, such as the King of Na, whose golden seal has been unearthed in 1784 nearby Fukuoka, and the famous queen Himiko, or Pimiko, whose identity has been an unsolved riddle still haunting the mind of the most invested scholars of Japan. This mythical figure, to whom we will dedicate an article very soon, was said to have brought peace in the land of Wa through her might, and to have used supernatural powers to manage her retainers. Whether Himiko existed or not, and whether her kingdom was located in Kyūshū or in the Kantō region might remain a mystery. However, little doubt remains that powerful kingdoms emerged after a period of brutal fighting, as it is also attested by archaeological findings.

Further Archaeological Proof of Troubled Times

Watchtower reconstruction from Yoshinogari Archeological site.

Many archaeological sites attributed to this period confirm the observations made by the Chinese historians. A common characteristic of Yayoi dwellings is their emplacement. The housings were elevated and often located in easily defendable higher-lying areas. It appears that protection over assailants was more important than the cultivation of land during the first two centuries of the common era. Subsequent sites are found closer to plains and fertile lands, implying that the unrest had decreased by the 3rd century.

The concentration of bronze items in specific sites also suggest the growth in prestige of a few chiefdoms. Bronze was a social marker of importance of an individual and its tribe in the complex hierarchical scheme of the time. Higher concentrations have mainly been found in the form of bronze weapons from north Kyūshū to the middle Inland Sea and in the form of bronze bells and mirrors in the Kinki and Kinai regions, further confirming the Chinese chronicles.

The three chiefdoms mentioned in the article below, the disputed Kibi region and the location of sites bearing traces of armed conflicts.

Base map provided by Google, infographic effectuated by Marty Borsotti.

The central region in particular was a disputed land between the southern Tsukushi tribes and the eastern Kinki tribes, as it was of strategic importance for controlling the traffic of materials. Southern tribes might have reacted to the expansion of the central ones, and conflicts seem to have occurred frequently, especially between the proto-Yamato chiefdom and the Izumo tribe, who halted its expansion. This interpretation was made possible due to archeological sites bearing evidence of armed conflicts, one among many is the Katsube site in Osaka, which features two bodies bearing signs of a violent death. Similarly, signs of a massive increase in weapon production can be observed all over the Yayoi sites from the 1st and 2nd centuries A.C., that can not simply be explained through hunting practices. Tools initially conceived for hunting were progressively developed to become offensive weapons, mainly made out of stone and including a few rarer iron and bronze items as well. However, by the 3rd century, the abundance of weapons diminished again and many bronze items reverted back to their symbolic functions. As chiefdoms grew in size and population, it is likely that military politics became too demanding in resources and slowly gave way to more elaborate diplomatic strategies. One of these diplomatic attempts has been transmitted in the form of the Japanese national myths, which compilation might offer hints on how the chieftains of the proto-Yamato kingdom tried to gain the allegiance of neighbouring tribes.

Japanese Sources: Between Mythology, Legend and an Attempt at Historiography

The Kojiki and Nihon-shoki, two chronicles of Japanese history, commissioned by the ruling emperor of the Nara capital, were meant to narrate the mythical and pseudo-historical expansion of the Yamato kingdom. Both documents also served the purpose of establishing the divine lineage of the imperial family as descendants from the sun goddess Amaterasu. The emperor Tenmu, who commissioned the chronicles, was naturally the most recent member of that divine lineage. We will dedicate several articles to the Kojiki, the Nihon-shoki and Japanese mythology in due time. Nonetheless, some passages further confirm the reality of the troubled period we presented so far through figurative and mythological speech.

Emperor Jinmu - Stories from "Nihon Shoki" (Chronicles of Japan) 1891, by Ginko Adachi.

Woodblock print depicting legendary first emperor Jimmu, who saw a sacred bird flying away while he was in the expedition of the eastern section of Japan.

It is through the legendary figure of the Emperor Jimmu and his acts that we can plausibly observe the violent expansion of the chiefdom that eventually became the Yamato kingdom. The emperor is said to have moved from Kyūshū to the north, where he encountered resistances as soon as he reached the Kibi and Kinki regions. The fiercest opponent was probably the tribe of Izumo, lead by the chieftain Okuninushi, who forced Jimmu to frequently ask for the help of the deities. That tribe must have been extremely powerful because its might lead storytellers and historians to establish a kinship relation between Izumo and the ruling chiefdom of Yamato. According to the genealogy presented in both the Kojiki and the Nihon-shoki, Izumo is said to have been founded by the deity Susano-o, brother of the sun goddess Amaterasu, and Okuninushi was said to be one of his descendants. Therefore, according to what became the official narrative, the Izumo and Yamato tribes were bound to eventually form an allegiance. Moreover, to simplify the cosmogony of the Shinto cult of Ise, Okuninushi posthumously integrated this system of belief in the form of a mythical regalia, which signifies the ultimate reconciliation of what has been depicted as a fraternal conflict. This development likely represented the intention of the Yamato kingdom to ensure a solid allegiance with the strong Izumo tribe. By including another tribe in their religious and political structure, the Yamato kingdom strengthened established alliances. Similar elaborations have been made for many other tribes as well.

Okuninushi bronze statue at Izumo shire, in Izumo city, Shimane prefecture. ©Flow in edgewise

What we presented here is nothing but a simplified article trying to summarize a topic of far greater complexity. We merely scratched the surface of centuries, almost millennia, of scholarly works, both Japanese and international. The purpose of this article was to introduce you, our dear reader, to the many possible ways of observing the inception of what became the first political centre of Japan. As our journey through history will navigate us to many more complex topics, we will not fail to provide you with additional materials. Like this, you can further investigate what we mention in our articles, which are bound to a shorter format. Therefore, for the very first time, we present you two works that provided the core of this article: ‘The Location of Yamatai: a Case Study in Japanese Historiography’ (1958) by Jhon Young and ‘Himiko and Japan’s Elusive Chiefdom of Yamatai’ (2007) by J. Edward Kidder Jr.

Our time here has come to an end and our next meeting will be dedicated to the legendary figure of Queen Himiko. Next month, we will take a break from our regular publications to present to you some Japanese festivities and a special dossier about O-bon. So stay tuned for more discoveries!

_______________________________________________________________________

[1] Kidder, J. Edward. 2007. Himiko and Japan’s Elusive Chiefdom of Yamatai Archaeology, History, and Mythology. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, p.12-14.

Written By Marty Borsotti

![The incipit of the Wajinden reads ‘the Japanese people (the Wajiri) are located in the Lo-lang seas, have more than 100 states, and are periodically received [at the Lo-lang court]’.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5eaabc4f9a004e60a011f800/1621672945882-UI83DTJMIVAB72IGMW10/wajinden.jpg)

![Reproduction of the Golden seal with the inscription 漢委奴國王 ([the Dynasty] Han, [Land of] Wa, [Kingdom of] Na, State, Ruler), probably hinting at an official recognition from the Han emperor of the authority of the King of Na over his kingdom.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5eaabc4f9a004e60a011f800/1621673966068-UQZ21KRZW2MPWUJKINDQ/King_of_Na_gold_seal_face.png)